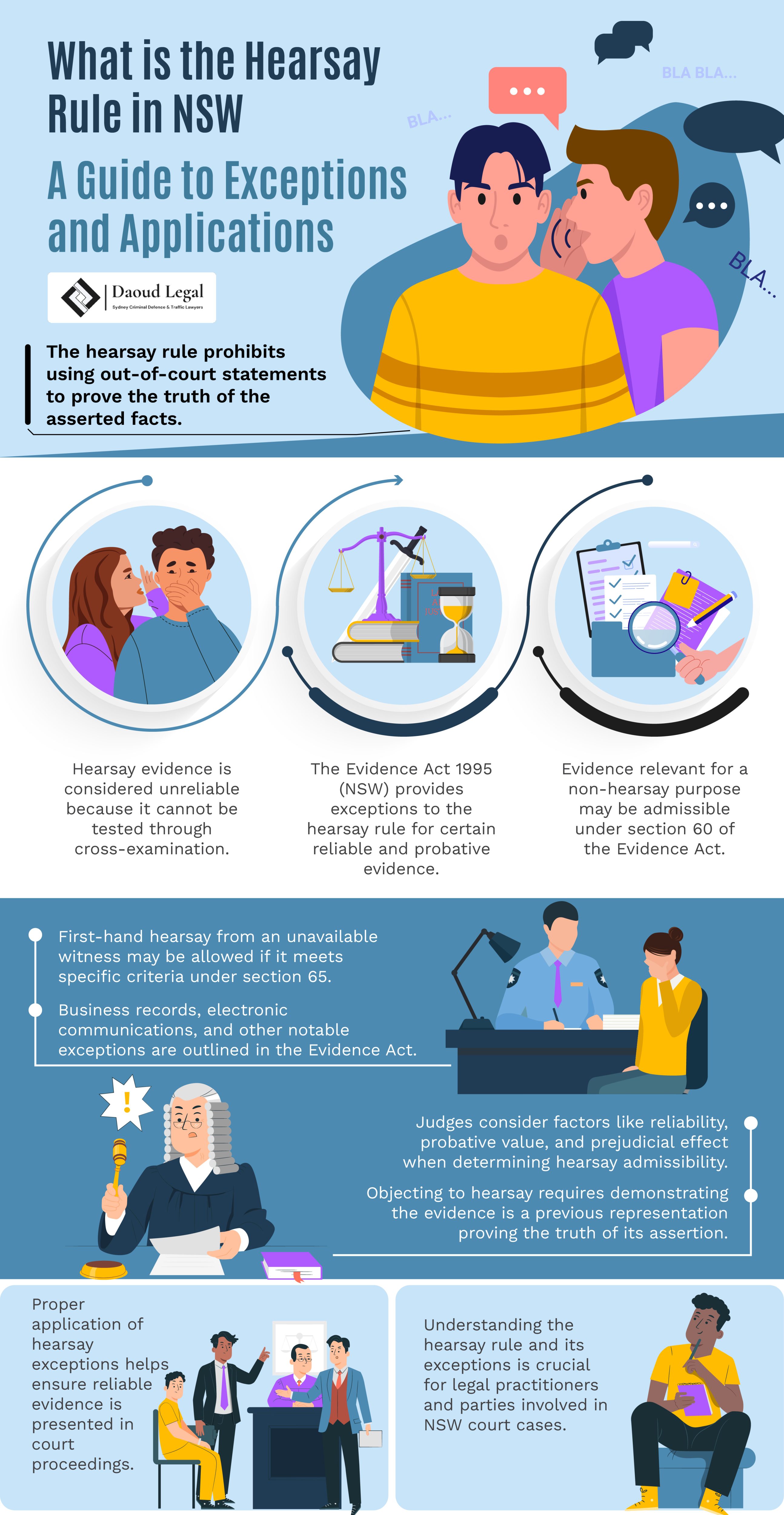

The hearsay rule is a fundamental principle of evidence law that prohibits the admission of out-of-court statements to prove the truth of the asserted facts. In NSW, the hearsay rule is codified in section 59 of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) and applies to both civil and criminal proceedings. The rationale behind this exclusionary rule is that hearsay evidence is generally considered unreliable, as it cannot be tested through cross-examination.

However, the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) also provides numerous exceptions to the hearsay rule, recognising that certain types of hearsay evidence may be sufficiently reliable and probative to warrant admission. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the hearsay rule, focusing on its key exceptions and their practical applications in legal proceedings. By understanding the nuances of the hearsay rule and its exceptions, legal practitioners can effectively navigate the complexities of adducing evidence and mounting objections based on hearsay grounds.

What is Hearsay Evidence?

Hearsay evidence is a statement made outside of court that is offered in court as evidence to prove the truth of the matter asserted in the statement. The hearsay rule is outlined in section 59 of the Evidence Act 1995, which states that evidence of a previous representation made by a person is not admissible to prove the existence of a fact that it can reasonably be supposed that the person intended to assert by the representation.

The hearsay rule exists because such evidence is considered unreliable, as it relies on the credibility of a person who is not testifying in court and therefore cannot be cross-examined. Hearsay evidence is generally not admissible in court proceedings unless an exception to the hearsay rule applies.

The Hearsay Rule

Section 59 of the Evidence Act 1995 sets out the hearsay rule, which applies to both civil and criminal proceedings in NSW. The rule prohibits the admission of evidence of a previous representation made by a person to prove the existence of a fact that the person intended to assert by the representation.

For example, if a witness testifies that they heard another person say that they saw the accused commit a crime, this would be considered hearsay evidence and would not be admissible to prove that the accused actually committed the crime. The witness’s testimony could only be used to establish that the other person made the statement, not to prove the truth of what was said.

First-Hand vs More Remote Hearsay

Hearsay evidence can be classified as either first-hand or more remote hearsay. First-hand hearsay is a statement made by a person who has direct knowledge of the fact asserted, such as an eyewitness to an event. More remote hearsay, also known as second-hand hearsay, is a statement made by a person who does not have direct knowledge of the fact asserted but rather heard it from another source.

First-hand hearsay is generally considered more reliable than more remote hearsay, as there is less opportunity for the information to be distorted or misinterpreted as it is passed from one person to another. However, even first-hand hearsay is still subject to the hearsay rule and is inadmissible unless an exception applies.

The distinction between first-hand and more remote hearsay is important when considering the exceptions to the hearsay rule outlined in the Evidence Act 1995, as some exceptions apply only to first-hand hearsay while others apply to both first-hand and more remote hearsay.

Get Immediate Legal Help Now.

Available 24/7

Exceptions to the Hearsay Rule

The Evidence Act 1995 establishes several key exceptions when hearsay evidence may be admissible in court proceedings. These exceptions recognise that certain types of hearsay evidence can be reliable and necessary for proving facts in legal matters.

Evidence Relevant for a Non-Hearsay Purpose

Under section 60 of the Evidence Act 1995, evidence of another person’s statement may be admitted if it serves a purpose other than establishing the truth of the statement. For example, in an intimidation case, evidence of what the accused said can be admitted to prove that statements were made, rather than to prove the truth of those statements. Once admitted for this non-hearsay purpose, the evidence can then be used to prove the truth of the statement.

First-Hand Hearsay Exceptions

First-hand hearsay evidence may be admissible when the maker of the representation has personal knowledge of the asserted fact. Section 65 allows first-hand hearsay if the person who made the statement is unavailable to give evidence and the statement was:

- Made under a duty to make that kind of representation

- Made at or shortly after the event occurred, in circumstances making fabrication unlikely

- Made in circumstances that make it highly probable the statement is reliable

- Against the interests of the person making it, in circumstances indicating reliability

When the maker of the representation is available, section 66 permits first-hand hearsay evidence if the matter was fresh in their memory when the representation was made.

Other Notable Exceptions

The Evidence Act provides additional exceptions to the hearsay rule, including:

- Business records and electronic communications

- Tags and labels attached to objects in the course of business

- Evidence about relationships and age

- Evidence of reputation regarding public or general rights

- Evidence in interlocutory proceedings when the source is identified

Practical Examples of Hearsay Applications

To illustrate how the hearsay rule and its exceptions apply in real court cases, let’s examine a few practical examples:

Consider a case where Person A is charged with assaulting Person B. If Person C testifies that Person B told them about the assault, this would generally be inadmissible hearsay. However, if Person B testifies in court about the assault and is cross-examined, their prior consistent statement to Person C may become admissible to rebut a suggestion that their testimony was a recent fabrication.

In another scenario, imagine the prosecution seeking to admit a witness’s written statement about seeing the accused commit a robbery, but the witness is unavailable to testify. Under section 65 of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW), this first-hand hearsay evidence may be admissible if the prosecution proves the witness is unavailable and the statement was made shortly after the alleged incident in circumstances that make it unlikely to be a fabrication.

As a third example, suppose an accused person is charged with making a threat to kill someone. If a witness testifies that they heard the accused make the threat, this evidence would not be hearsay because it is being used to prove the threat was made, not the truth of the threat itself.

Finally, in a case involving a larceny charge, a witness’s testimony about overhearing the accused admit to the theft could potentially fall under the hearsay exception for admissions under section 81 of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW).

These examples demonstrate how the hearsay rule and its various exceptions come into play in different criminal cases. Understanding these nuances is crucial for legal practitioners when determining the admissibility of evidence and building effective case strategies.

Speak to a Lawyer Today.

Available 24/7

Admissibility Challenges

Determining the admissibility of hearsay evidence requires careful consideration of complex legal principles under the Evidence Act 1995. The court must assess whether the evidence falls within the scope of section 59 and if any exceptions apply that would allow the evidence to be admitted.

Objecting to Hearsay Evidence

When hearsay evidence is presented in court proceedings, parties can object to its admission under section 59(1) of the Evidence Act 1995. The objection must be raised at the time the evidence is sought to be introduced. A valid objection requires demonstrating that the evidence is a previous representation being used to prove the truth of what it asserts.

The party seeking to admit the hearsay evidence must then establish whether any exceptions apply that would make the evidence admissible. For instance, if the evidence is relevant for a non-hearsay purpose under section 60, or if it qualifies as first-hand hearsay from an unavailable witness under section 65.

Judicial Discretion and Interpretation

Judges play a key role in determining whether hearsay evidence should be admitted. They must consider factors such as:

- The reliability of the evidence and circumstances in which the representation was made

- Whether the evidence falls within established exceptions to the hearsay rule

- The probative value of the evidence versus its potential prejudicial effect

- The availability of other evidence to prove the same facts

The court may admit hearsay evidence if satisfied it was made shortly after the asserted event occurred and in circumstances making fabrication unlikely. For example, if a witness made a statement immediately after observing an incident, while the events were fresh in their memory.

Conclusion

The hearsay rule and its exceptions form a complex but essential part of evidence law in NSW. The Evidence Act 1995 provides clear guidelines on when hearsay evidence may be admissible, particularly in cases where the evidence serves a non-hearsay purpose or meets specific exception criteria.

Understanding these rules is vital for legal practitioners and parties involved in court proceedings. The proper application of hearsay exceptions, from first-hand hearsay to business records and electronic communications, helps ensure reliable evidence is presented while maintaining the integrity of the legal process.

Get answers to your legal questions—schedule a consultation today