Introduction

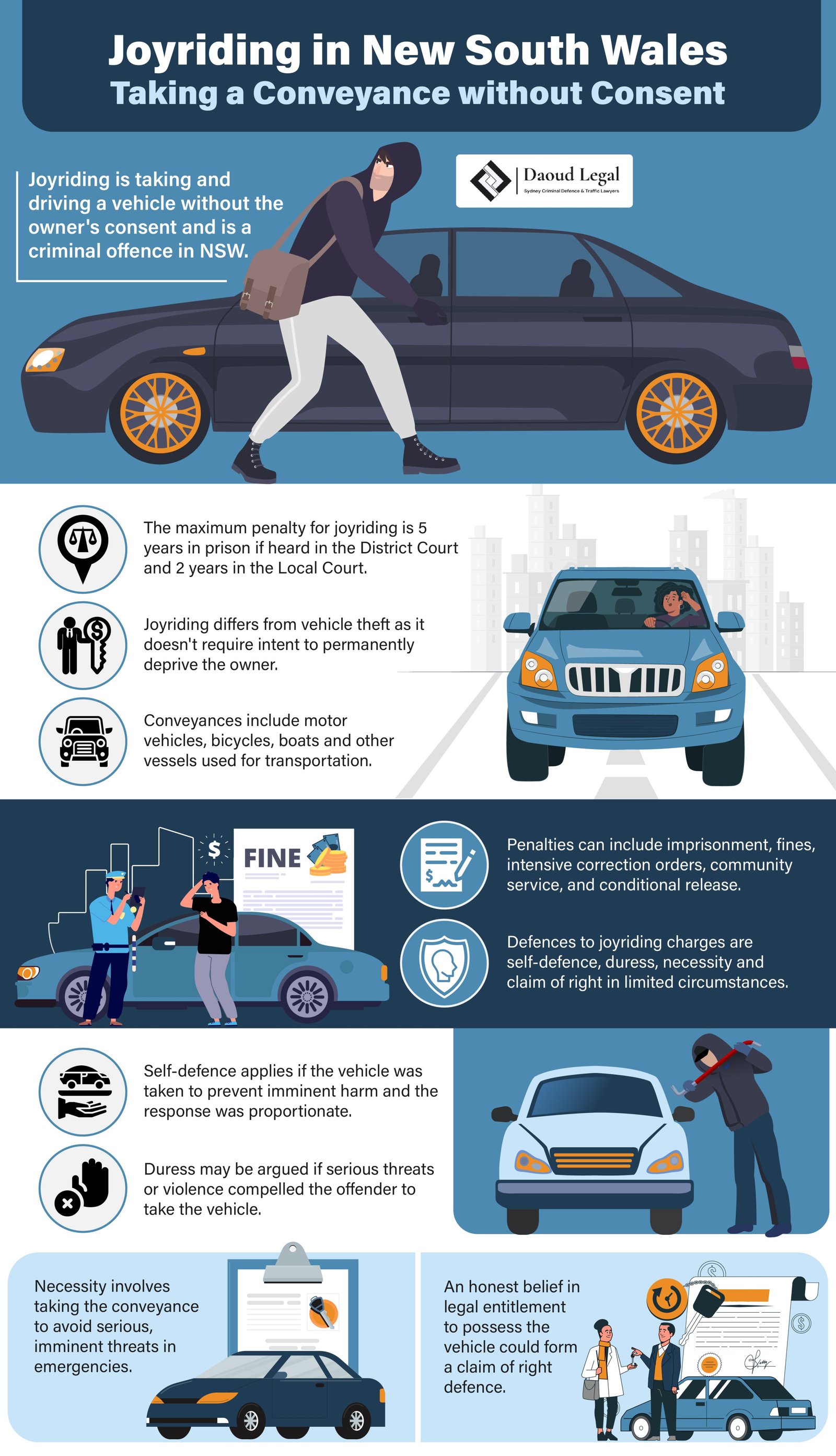

Joyriding, defined as taking a conveyance without the owner’s consent, is a criminal offence in New South Wales (NSW). Governed by section 154A of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW), this offence carries significant penalties, including imprisonment and fines. Understanding the legal implications and the severity of joyriding is essential for both vehicle owners and individuals who might be at risk of committing this offence.

For those facing joyriding charges or seeking to comprehend the legal landscape surrounding this offence in NSW, this guide provides comprehensive insights. By exploring the definitions, penalties, and distinctions between joyriding and more severe charges like vehicle theft, readers can better navigate the complexities of NSW law and equip themselves against potential litigation.

Definition of Joy Riding under NSW Law

Legal Definition and Scope

Joyriding, legally referred to as taking a conveyance without the consent of the owner, is defined under section 154A of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW). This offence involves taking and driving a conveyance without permission, for the purpose of driving, secreting, obtaining a reward for its restoration or pretended restoration, or using it for any other fraudulent purpose. This offence also extends to those who, knowing the conveyance has been taken without consent, drives it or allows themselves to be a passenger. In NSW, a conveyance encompasses a vast range of vehicles, including motor cars, lorries, bicycles, and vessels used or intended for navigation.

Classification as a Criminal Offence

Get Immediate Legal Help Now.

Available 24/7

Under NSW law, joyriding is classified as a criminal offence of larceny, which underscores the seriousness of unlawfully taking and using someone else’s vehicle without consent. This classification subjects offenders to significant penalties, reflecting the legal system’s stance on protecting property rights. joyriding differs from the offence of stealing a motor vehicle or vessel, which typically involves the intention to permanently deprive the owner of their property. While both offences involve taking a conveyance without consent, joyriding is often perceived as less severe when the vehicle is later returned, whereas stealing implies a permanent loss to the owner.

Penalties for Taking a Conveyance Without the Consent of the Owner

Taking a conveyance without consent in NSW can lead to a range of penalties, including significant custodial sentences, which means being detained in a correctional facility. Typically, these cases are heard in the Local Court, which is suitable for less severe situations. However, if the case is deemed sufficiently serious, involves complex legal issues, or if the defendant elects to have the matter heard in a higher court, it may be heard in the District Court.

Custodial Penalties

A guilty verdict for joyriding may include a custodial sentence. The maximum penalty for joyriding is five years imprisonment if prosecuted in the District Court. In the Local Court, the maximum penalty is up to two years imprisonment and/or a $5,500 fine. For individuals with prior convictions or under aggravating circumstances, the court may impose a full-term custodial sentence, resulting in detention in a correctional facility.

Non-Custodial Penalties

Non-custodial penalties offer alternatives to imprisonment, aiming to rehabilitate offenders while minimising disruption to their lives. These penalties include:

| Penalty type | Description |

| Fines | Courts may impose monetary penalties based on your financial situation and your ability to pay any fine they set, as well as the severity of the offence. |

|

Intensive Correction Order (ICO) |

Replaces periodic detention with conditions such as attending counselling, abstaining from alcohol, having a curfew, and performing community service. Home detention may also be imposed as a condition for an ICO, and is essentially serving a jail sentence at your address under strict supervision and electronic monitoring. |

|

Community Corrections Order (CCO) | A CCO includes the standard conditions that an offender must not commit any offence and that the offender must appear before the court if called on to do so at any time during the term of the CCO. A variety of additional conditions may also be imposed at the discretion of the court at the time of sentence, or a community corrections officer upon application. These include: a curfew, community service work, rehabilitation or treatment, abstention from using drugs and/or consuming alcohol, and more. |

|

Conditional Release Order (CRO) | A CRO involves standard conditions that an offender must not commit any further offences and must appear in court if called to do so, and almost have the same potential additional conditions as a CCO, except without the possibility of curfew or community service. A CRO can be viewed as very similar to a good behaviour bond. |

| Section 10 Dismissals | In certain cases, the court may find the offence proven, but dismiss the matter under section 10 of the Crimes (Sentencing & Procedure) Act 1999 (NSW). There are a few types of these dismissals. A Section 10(1)(a) dismissal dismisses the matter without imposing any conditions whatsoever, while a Section 10(1)(b) dismissal imposes a CRO on the offender. Similarly, a Section 10(1)(c) dismissal imposes conditions on the offender, but they are only to agree to participate in an intervention program and comply with its plan. |

Speak to a Lawyer Today.

Available 24/7

Legal Defences Against the Offence

Self-Defence

Self-defence can be a viable defence in joyriding cases where the defendant can demonstrate that they took the conveyance without consent to protect themselves or others from imminent harm. For this defence to be applicable, the force used must be proportionate to the threat faced. This means the force cannot exceed the threat in severity, but can only match it. For example:

- Protecting Against Physical Harm: If you are forced to take a vehicle to defend yourself or someone else from an aggressor, you may be able to claim self-defence.

- Preventing Property Damage: Using the vehicle to prevent imminent damage to your own or others’ property may constitute self-defence.

Necessity

Similarly to self-defence, it may be necessary to take a conveyance to protect oneself, someone else, or property against a threat of imminent harm. However, it need not be by an aggressor or be unlawful, but must be nonetheless threatening, for example, in an incoming natural disaster. It should be noted that the standard of necessity may be difficult to meet, and may fall short if the threat is not life-threatening.

Duress

Duress involves being compelled to perform an act due to immediate threats or harm, thereby negating criminal intent, which thereby likely negates the conviction, since criminal intent is normally required for criminal cases. In joyriding cases, if the defendant was forced under constrained circumstances to take and drive the conveyance due to a threat of serious violence, duress may be used as a defence. Key points include:

Immediate Threat: The threat must be of immediate harm, leaving no reasonable opportunity to escape. That is, the conveyance without consent must have been a necessarily immediate response to the threat, which was unavoidable.

- Lack of Reasonable Alternative: The defendant must show that taking the conveyance was the only available option to avoid the threat. Whether this is reasonable is assessed by contemplating whether or not “a person of ordinary firmness” would have done similarly in similar circumstances, meaning, whether or not the action was a regular, rational decision. It must be noted that this can be a precarious standard to prove.

It should also be noted that duress fails where the accused voluntarily exposed themselves to duress, such as by affiliating with a criminal group.

Claim of Right

Since a lack of criminal intent may negate a conviction, demonstrating a genuinely and honestly belief that the conveyance was your lawful possession, and not taken without consent, can be a viable defence.

- Importantly, this belief must be one of legal entitlement, and not merely a moral entitlement, that is, not thinking you personally deserve to possess something.

- Further, this belief must extend to the entirety of the conveyance, not just a part.

- While these beliefs do not need to be true in law or fact, or even reasonable, they must not be a “colourable pretence”, that is, it cannot be a belief that you might have a right to the conveyance, but rather, an actual belief.

These defences require the defendant to provide evidence that the offence was committed under circumstances beyond their control and that they had no reasonable alternative but to act as they did, or that they believed they committed no offence.

Conclusion

Understanding the legal implications of joyriding in NSW is essential for both vehicle owners and individuals who might be at risk of committing this offence. Joyriding, defined under section 154A of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW), carries significant penalties, including imprisonment and fines, and is distinct from the more serious offence of stealing a motor vehicle or vessel.

Knowing what constitutes joyriding affords the opportunity to avoid committing the offence, and if you already have or are at risk, knowing viable defences and options in litigation is vital to protect yourself from weighty custodial and non-custodial penalties. Having this sort of knowledge makes it easier to correspond with a legal representative if you are at risk.