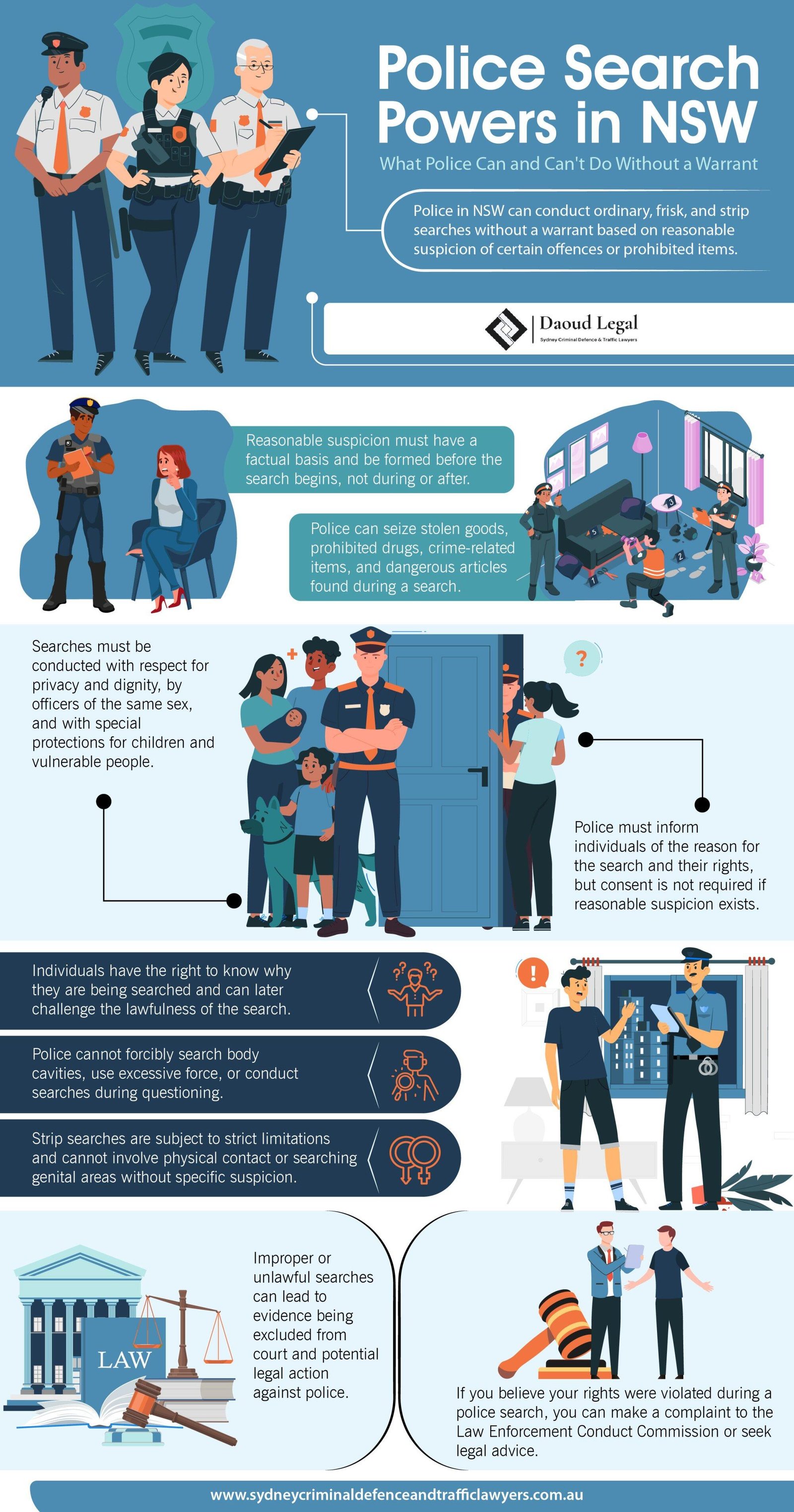

Police in New South Wales can search people and their belongings without a warrant thanks to the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW). This ability helps police to stop and look into crimes quite effectively. However, there are tight rules set to ensure people’s rights and privacy are not overlooked. Curious about the ins and outs of this? Let’s dive in and uncover some surprising details on how these laws work.

Understanding the scope and limits of police search powers is crucial for both law enforcement and members of the public. This article will provide a comprehensive overview of when and how police can conduct searches without a warrant in NSW, focusing on the different types of searches, the concept of reasonable suspicion, and the rights of individuals during these encounters.

Types of Police Searches and Legal Basis

Police searches in New South Wales are governed by the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW). This legislation outlines the different types of searches police can conduct and the circumstances under which they are permitted.

Ordinary Searches

An ordinary search involves a search of a person or their belongings, including an examination of any items in their possession. Police may require the removal of outer clothing such as coats, jackets, gloves, shoes, socks, and hats during an ordinary search (LEPRA s 30). To conduct an ordinary search without a warrant, police must suspect on reasonable grounds that the person possesses stolen goods, prohibited drugs, items used in committing an offence, or dangerous articles (LEPRA s 21).

Frisk Searches

A frisk search involves police quickly running their hands over a person’s outer clothing or using an electronic metal detection device. It may also include examining items voluntarily removed by the person (LEPRA s 30). Like ordinary searches, police must have reasonable suspicion to conduct a frisk search without a warrant (LEPRA s 21).

Strip Searches

Strip searches are more invasive and involve the removal of some or all of a person’s clothing for visual inspection. Police must suspect on reasonable grounds that a strip search is necessary for the purposes of the search, and that the seriousness and urgency of the circumstances require it (LEPRA s 31).

Strict rules apply to strip searches:

- They must be conducted in a private area by an officer of the same sex (LEPRA s 32)

- Police must inform the person why the search is necessary (LEPRA s 32)

- Children under 10 cannot be strip searched (LEPRA s 33)

- A parent, guardian or support person must be present for searches of children aged 10-18 or persons with intellectual impairment, unless the person objects (LEPRA s 33)

The invasiveness of strip searches means they are subject to greater scrutiny. Police must ensure the search is no more invasive than reasonably necessary in the circumstances.

In summary, while police have broad search powers under LEPRA, these powers are not unlimited. Searches must be justified based on reasonable suspicion, and specific rules govern how each type of search is conducted to protect individual rights. Understanding the legal basis and limitations of police search powers is crucial for both law enforcement and members of the public.

Police Powers to Search Without a Warrant

Police in NSW have the power to search individuals without a search warrant under certain circumstances, as outlined in the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW). These powers are based on the concept of “reasonable suspicion” and apply to searches conducted in public places, schools, and vehicles.

Reasonable Suspicion

The key factor enabling police to search without a warrant is “reasonable suspicion.” As defined in the landmark case R v Rondo, reasonable suspicion “involves less than a reasonable belief but more than a possibility.” The suspicion must have a factual basis and cannot be based on hearsay or speculation. Importantly, the suspicion must be formed before the search begins, not during or after the search.

Factors that alone do not constitute reasonable suspicion include:

- Appearing nervous

- Being in the company of suspected drug users

- Being in an area associated with drug use, such as a music festival

Searches in Public Places

Under Section 21 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW), police may stop, search, and detain a person in a public place if they suspect on reasonable grounds that the person possesses:

- A prohibited plant or drug

- Stolen or unlawfully obtained items

- Items used or intended for use in a crime

- Dangerous articles used in a crime

Police may also require a person to open their mouth or move their hair if they suspect items are concealed there. However, police cannot forcibly open a person’s mouth.

In schools, police can search students’ bags, effects, and lockers. When possible, police should allow the student to nominate an adult to be present during the search.

Vehicle Searches

Police have the power to stop and search vehicles if they reasonably suspect the vehicle contains stolen items, items used in a crime, dangerous articles, or prohibited plants or drugs. This power extends to searching any person in or on the vehicle.

When conducting searches without a warrant, police must adhere to strict guidelines to protect individuals’ rights and dignity. Failure to follow these rules may result in any discovered evidence being excluded from court proceedings.

Get Immediate Legal Help Now.

Available 24/7

What Police Can Do During a Search

Seizing and Detaining Items

During a search, police have the power to seize and detain certain items found in a person’s possession. According to Section 21 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW), police may seize:

- Anything stolen or otherwise unlawfully obtained

- Anything used or intended to be used in connection with the commission of an offence

- A dangerous article (firearm, toxic chemical, explosive) that is being or was used in connection with the commission of an offence

- Prohibited plants or prohibited drugs

If police suspect on reasonable grounds that a dangerous article found during a search is being or was used in connection with an offence, they have the right to seize and detain that article.

Use of Force

While police have broad search powers, there are limitations on the use of force during searches. As per Section 230 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW), police must not use more force than is reasonably necessary to exercise a function under this Act.

When conducting a search, Section 30 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW)allows police to:

- Quickly run their hands over the person’s outer clothing

- Require removal of coat, jacket, gloves, shoes, socks and hat (but not all clothes unless it is a strip search)

- Examine anything in the person’s possession

- Pass an electronic metal detection device over the person’s outer clothing or belongings

- Do any other thing authorised by the Act for the search purpose

However, police cannot forcibly open a person’s mouth to search it. If a person refuses a lawful request to open their mouth for a search, they may face a fine of up to $550.

The key principle is that police must conduct the least invasive search practicable in the circumstances and use only as much force as reasonably necessary. Excessive force during a search could constitute assault and be grounds for a complaint or legal action against the officer.

What Police Can’t Do During a Search

While police have certain powers to conduct searches under the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW), there are important limitations on what they can do during these searches. Police must adhere to specific rules designed to protect the rights and dignity of the person being searched.

Privacy and Dignity Considerations

Section 32 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW)outlines several key requirements police must follow to preserve privacy and dignity during searches:

- Police must ask for your cooperation and inform you whether you will need to remove clothing and why it is necessary.

- The search must be conducted in a way that provides reasonable privacy and as quickly as possible.

- Police can only conduct the least invasive kind of search necessary under the circumstances.

- Searches must be carried out by an officer of the same sex as the person being searched. If no such officer is available, the search may be delegated to another person of the same sex.

- Searches cannot be conducted during questioning.

- The person must be allowed to dress as soon as the search is finished. If clothing is seized, police must ensure the person has reasonably appropriate clothing.

Additionally, police cannot search your genital area or breasts unless they have a reasonable suspicion that it is necessary for the purposes of the search.

Restrictions on Strip Searches

Strip searches are subject to even stricter limitations under the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW)due to their highly invasive nature:

- Children under 10 years old cannot be strip searched.

- Strip searches must be conducted in a private area, out of view of people of the opposite sex or anyone whose presence is not necessary for the search.

- A parent, guardian, or personal representative may be present during a strip search if the person being searched does not object.

- For children between 10–18 years old or persons with impaired intellectual functioning, a parent or guardian must be present. If the person objects, another capable person must be present to represent their interests.

- Strip searches cannot involve searching body cavities or examining the body by touch.

- Police can only request the removal of clothing reasonably necessary for the search and conduct visual inspection no more than is reasonably necessary.

It’s important to note that police must have your consent before conducting a strip search and provide evidence of their identity as a police officer. Conducting a strip search without consent could constitute assault.

If you believe your rights have been violated during a police search, you can make a complaint to the Law Enforcement Conduct Commission (LECC), which provides independent oversight of police misconduct in NSW. Understanding these limitations on police search powers is crucial for protecting your rights in any encounter with law enforcement.

Your Rights During a Police Search

When being searched by police, it’s important to know your rights. The police must follow certain procedures to ensure that searches are conducted lawfully and with respect for your privacy and dignity.

Right to Information

Before conducting a search, police must provide you with certain information. According to Section 201 of the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW), the police officer must:

- Provide evidence that they are a police officer, such as showing their police identification.

- Inform you of their name and place of duty.

- Explain the reason for the search.

- Warn you that failure to comply with the search may be an offence.

The police must ask for your cooperation and inform you whether you will be required to remove clothing during the search and why it is necessary.

Right to Refuse Consent

While you can refuse consent for a search, this does not necessarily mean the police cannot search you. If police have a valid reason, such as reasonable suspicion under the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW), they can still conduct the search without your consent.

However, you should never expressly give consent, even if you are complying with police instructions. If you consent, police do not need to prove they had reasonable grounds to search you.

It’s important to remain calm and cooperative during the search process, even if you have not consented. If you believe the search was unlawful, you can lodge a complaint or challenge the search later. Resisting the search at the moment could lead to charges of resisting or hindering police.

In summary, while you generally cannot refuse a lawful search, you are not obligated to give active consent. Simply comply with instructions and be aware of your rights to ensure the police are following proper procedures. If you believe your rights have been violated, seek legal advice on your options to making a complaint.

Speak to a Lawyer Today.

Available 24/7

Implications of Improper Searches

When police conduct searches that do not comply with the law, there can be serious consequences. Improper searches can lead to evidence being excluded from court proceedings and potential legal action against the officers involved.

Exclusion of Evidence

Under section 138 of the Evidence Act 1995 (NSW), evidence obtained improperly or in contravention of Australian law may be excluded from court proceedings. This means that if police conduct an illegal search, any evidence they find may be inadmissible in court.

For example, if police search a person without reasonable suspicion as required by the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW), and find drugs in their possession, that evidence could be excluded. This could result in criminal charges being dismissed.

The court will consider factors such as the seriousness of the impropriety, whether the impropriety was deliberate or reckless, and the importance of the evidence in determining whether to exclude it.

Complaints and Legal Action

Individuals who believe they have been subjected to an unlawful search by police can make a complaint to the Law Enforcement Conduct Commission (LECC). The LECC is an independent body that oversees and investigates complaints about NSW Police misconduct.

Complaints can be made online via the LECC website. It’s important to include detailed statements and any supporting evidence. The LECC will assess the complaint and may investigate if it appears that serious misconduct has occurred.

In some cases, individuals may also have grounds to take legal action against police for improper searches. This could include civil claims for assault, battery or false imprisonment if the search involved the use of force or unlawful detention.

Complaints and legal action can lead to disciplinary action against police officers, changes to police practices, and compensation for those affected by improper searches. However, the process can be lengthy and challenging, so it’s important to seek legal advice.

Conclusion

In New South Wales, police officers have significant powers to search individuals without a warrant under the Law Enforcement (Powers and Responsibilities) Act 2002 (NSW). These powers are designed to help police prevent and investigate crimes, but they are also subject to important legal safeguards to protect individual rights and dignity.

Police can conduct ordinary searches, frisk searches, and strip searches based on reasonable suspicion of certain offences or possession of prohibited items. However, the law sets out strict rules for how these searches must be conducted, including requirements for privacy, same-sex officers, and special protections for children and vulnerable individuals. Understanding your rights during police searches, such as the right to know the reason for the search and the right to refuse consent, is crucial. If police conduct an unlawful or improper search, it can lead to evidence being excluded from court proceedings and potential legal action against the officers involved.

Let us handle the legal complexities. Reach out for a consultation.