Introduction

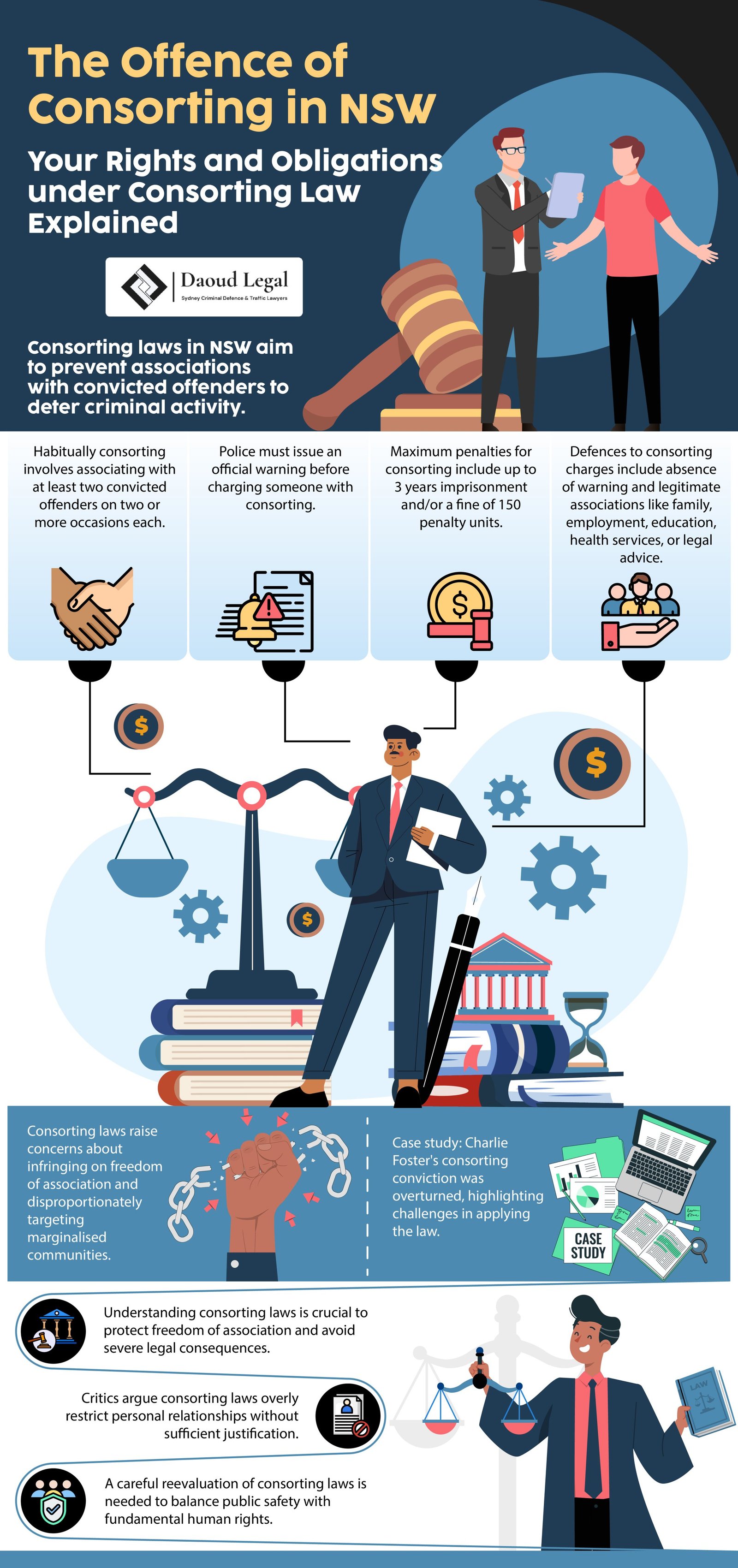

The crime of consorting in New South Wales is a law made to stop people from hanging out with convicted criminals, especially those linked to gangs. Under the Crimes Act 1900, this rule tries to stop crime by limiting talks that might lead to more bad acts.

Understanding the implications of consorting laws is crucial for individuals to safeguard their freedom of association and avoid severe penalties, including imprisonment and fines. This guide elucidates the legal framework, elements of the offence, available defences, and the broader impact on civil liberties, providing essential knowledge for those navigating the complexities of consorting regulations in NSW.

Definition and Legal Framework in NSW

Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) Section 93X

Section 93X of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) outlines the offence of consorting. According to this section, a person is guilty of the offence if they:

- Habitually consort with convicted offenders, and

- Consort with those convicted offenders after having been given an official warning in relation to each of those convicted offenders.

To be considered as habitually consorting, the individual must associate with at least two convicted offenders, and each association must occur on at least two separate occasions.

An official warning is a notice issued by a police officer, either verbally or in writing, informing the individual that the person they are consorting with is a convicted offender and that continuing to associate with them constitutes an offence.

Examples of Consorting

Practical examples of consorting include:

- Meeting with known criminals regularly: Meeting up with a group of bikers on a weekly basis after receiving written warnings against consorting with them.

- Employing individuals with criminal histories: Employing several people who have been identified by the police as repeat fraud offenders despite warnings not to associate with them.

Maximum Penalties

The maximum penalties for a consorting offence under Section 93X of the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW) are severe. An individual convicted of consorting can face:

- Imprisonment for up to three years, or

- A fine of 150 penalty units, or

- Both imprisonment and a fine.

These penalties reflect the seriousness with which NSW law treats the offence of consorting, aiming to deter individuals from associating with convicted offenders and thereby reducing the potential for organised criminal activity.

Elements of the Offence Explained

Habitual Consorting

Habitual consorting involves consistently associating with individuals who have been convicted of serious indictable offences. To meet this element, the prosecution must demonstrate that the defendant has consorted with at least two convicted offenders. Furthermore, each association must occur on two or more separate occasions.

Key factors defining habitual consorting include:

- Frequency of Association: Engaging with convicted offenders multiple times indicates a recurring pattern of behaviour.

- Nature of Associations: Interactions can occur in person or through other means, including electronic communication.

- Severity of Offences: The individuals consorted with must have been convicted of serious indictable offences, which carry a maximum penalty of five years imprisonment or more.

Official Warnings

Official warnings are a critical component in establishing the offence of consorting. Before an individual can be charged, police must issue a formal warning, informing them that consorting with a convicted offender is unlawful. These warnings can be delivered verbally or in writing, and must clearly state that associating with a convicted offender is an offence.

Key aspects of official warnings include:

- Clear Communication: The warning must explicitly inform the individual about the offence related to consorting with a convicted offender.

- Duration of Warning: For individuals under 18 years old, the warning expires after six months, whereas for those over 18, it remains valid for 24 months.

- Enforcement After Warning: Continued consorting after receiving an official warning can lead to charges for the offence of consorting.

By understanding these elements, individuals can better comprehend the legal requirements and implications associated with the offence of consorting in NSW.

Get Immediate Legal Help Now.

Available 24/7

Defences and Exceptions as per Consorting Laws

Absence of Warning

A primary defence against consorting charges is proving that the accused did not receive an official warning from the NSW police before associating with a convicted offender. Without such a warning, the prosecution may be unable to establish that the individual was aware that consorting was an offence under the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW). This lack of notification can undermine the basis for the charge, as the law requires that individuals be informed of the prohibition against consorting with convicted offenders.

Legitimate Associations

Certain associations are exempt from consorting offences if they fall within specific lawful exceptions outlined in the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW). To successfully utilise these exceptions, the defendant must demonstrate that their association was reasonable in the given circumstances. These legitimate associations include:

- Consorting with Family Members: Associating with immediate family members is not considered consorting, as familial relationships are inherently lawful.

- Lawful Employment or Business Operations: Interactions that occur within the context of legitimate employment or the lawful operation of a business are excluded from consorting offences.

- Training or Education: Associations formed during educational or training programs are deemed lawful and do not constitute consorting.

- Provision of Health Services or Legal Advice: Consorting that takes place in the course of providing health services or legal counsel is considered lawful.

- Lawful Custody or Court Order Compliance: Consorting while in lawful custody or while complying with a court order is exempt from consorting charges.

Each of these exceptions requires the defendant to satisfy the court that their association was reasonable and aligned with lawful activities.

Speak to a Lawyer Today.

Available 24/7

Impact on Freedom of Association

Human Rights Concerns

Consorting laws in NSW have raised significant human rights concerns, particularly regarding the infringement on individuals’ freedom of association. Critics argue that these laws overly restrict personal relationships and social interactions, potentially violating fundamental human rights. The ability to freely associate with others is a cornerstone of democratic societies, and when consorting laws are applied broadly, they can inadvertently limit this freedom without sufficient justification.

Key human rights issues associated with consorting laws include:

- Overreach of Police Powers: The broad discretion granted to police officers in determining when consorting constitutes an offence can lead to arbitrary enforcement, undermining the principles of justice and fairness.

- Lack of Proportionality: The severe penalties for consorting, such as imprisonment and substantial fines, may not proportionately reflect the nature of the offences, especially in cases where the association lacks criminal intent.

- Impact on Civil Liberties: By criminalising ordinary social interactions, consorting laws can impede individuals’ civil liberties, making it difficult for people to maintain personal and professional relationships without fear of legal repercussions.

These concerns highlight the tension between law enforcement objectives and the preservation of individual rights, urging a careful reevaluation of consorting laws to balance public safety with fundamental freedoms.

Targeting Marginalised Communities

Consorting laws have been criticised for disproportionately targeting marginalised and vulnerable communities, exacerbating social inequalities. Research indicates that these laws are often applied in ways that disadvantage-specific groups, including Aboriginal people, individuals experiencing homelessness, and youths. This selective enforcement undermines the principle of equal treatment under the law and can perpetuate systemic biases.

Key impacts on marginalised communities include:

- Disproportionate Enforcement: Aboriginal individuals are significantly overrepresented in consorting law enforcement actions, with statistics showing that police officers targeted them in 44 percent of cases where consorting laws were applied.

- Stigmatisation and Criminalisation: By focusing on disadvantaged groups, consorting laws contribute to the stigmatisation of these communities, reinforcing negative stereotypes and making rehabilitation and reintegration efforts more challenging.

- Barrier to Rehabilitation: The application of consorting laws to marginalised individuals can impede their access to support services and community programs aimed at reducing recidivism, thus counteracting broader crime prevention goals.

These issues underscore the need for a more equitable approach in the enforcement of consorting laws, ensuring that they do not disproportionately impact those who are already vulnerable, and promoting fairness within the criminal justice system.

Case Study: Charlie Foster

Overview of the Case

Charlie Foster, a 21-year-old man from Inverell with an intellectual disability, was charged with consorting under the Crimes Amendment (Consorting and Organised Crime) Bill 2012 (NSW). His alleged consorting involved three separate occasions where he interacted with convicted criminals, including bumping into them on the roadside and being seen sitting outside a hotel with the group.

Legal Outcomes and Implications

Foster was initially sentenced to 12 months imprisonment for his consorting offences. However, his conviction was later overturned by the NSW Supreme Court in April 2017. Justice Lucy McCallum ruled that the conviction was an “extremely narrow” application of the consorting laws, highlighting the challenges and potential misapplications of the legislation.

Conclusion

The offence of consorting in NSW serves as a critical tool in preventing organised crime by restricting associations with convicted offenders. Understanding these laws, including the legal definitions, maximum penalties, and possible defences, is essential for individuals to navigate their rights and obligations effectively.

The application of consorting laws can have profound impacts on personal freedoms and community dynamics, particularly as these laws have been criticised for disproportionately targeting marginalised groups. By being informed about the implications of consorting provisions under the Crimes Act 1900 (NSW), individuals can better protect their freedom of association and avoid severe legal consequences.