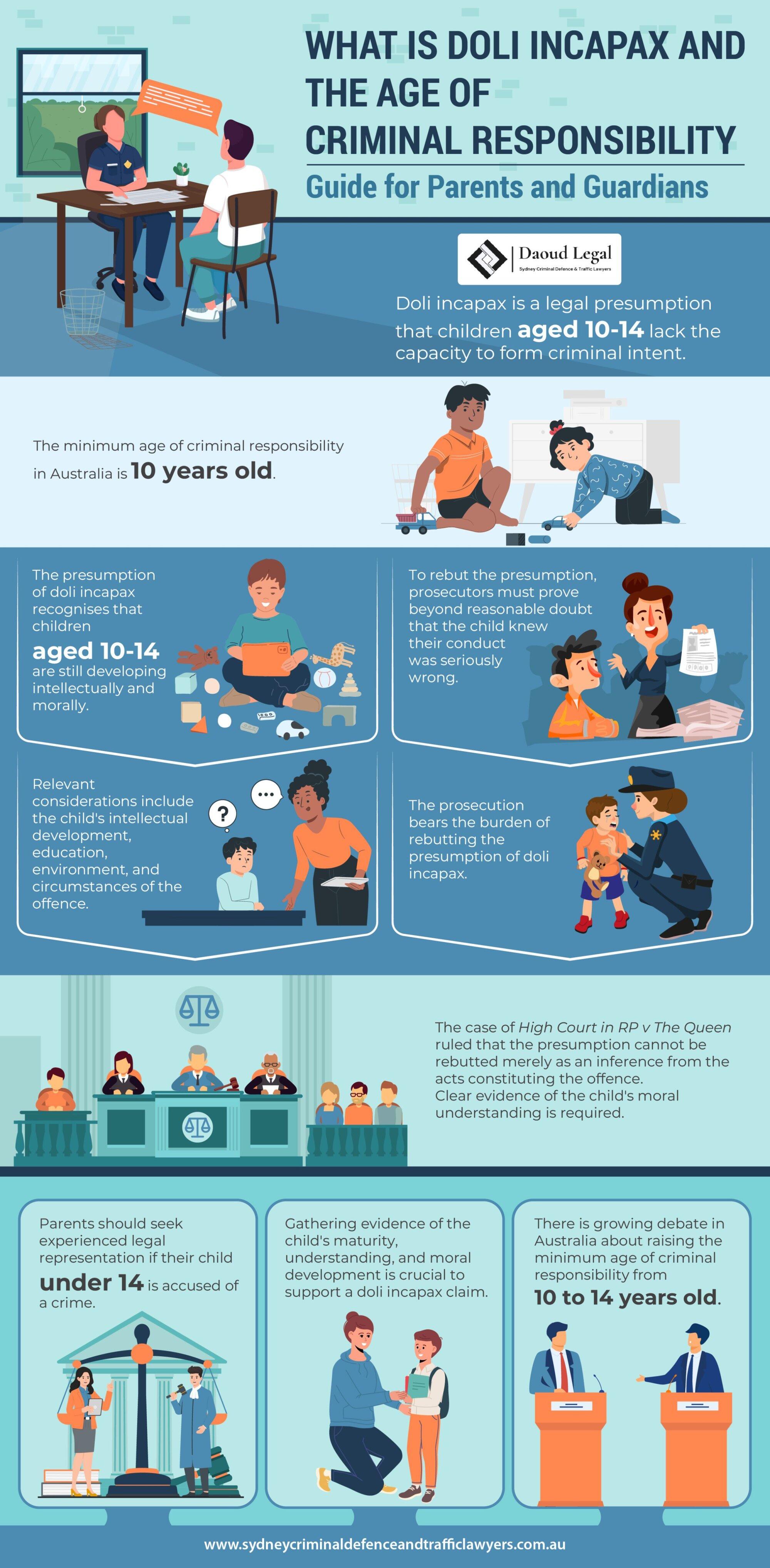

The legal idea of doli incapax assumes kids aged 10 to 14 can’t really form criminal intent. This common law notion tries to shield youngsters who might not grasp the gravity and fallout of what they’ve done from the whole weight of the justice system.

However, this presumption is rebuttable, meaning that prosecutors can present evidence to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that the child knew their conduct was seriously wrong in a moral sense. As a parent or guardian, it’s crucial to understand how doli incapax and the age of criminal responsibility apply if your child is accused of committing a crime.

What is Doli Incapax?

Doli incapax is a Latin term meaning “incapable of evil”. It is a legal presumption that children aged between 10 and 14 years are incapable of committing a crime due to a lack of understanding of the difference between right and wrong.

The Presumption of Doli Incapax

Under the common law, there is a presumption that children aged between 10 and 14 years do not possess the necessary knowledge to have criminal intentions. This means they are presumed to lack the capacity to be criminally responsible for their actions.

The presumption of doli incapax recognises that children in this age group are still developing intellectually and morally. It assumes they may not fully comprehend the seriousness and consequences of their behaviour

However, the presumption of doli incapax is rebuttable. The prosecution can lead evidence to prove beyond reasonable doubt that the child knew their conduct was seriously wrong in a moral sense, as opposed to merely naughty or mischievous.

The Age of Criminal Responsibility in Australia

In all Australian jurisdictions, the minimum age of criminal responsibility is 10 years old. This means that children under the age of 10 cannot be held criminally responsible for any offence.

Between the ages of 10 and 14, the presumption of doli incapax applies. If the prosecution wants to rebut this presumption, they must prove the child understood that their actions were seriously wrong.

Once a child turns 14, they are considered to have reached the age of full criminal responsibility. The presumption of doli incapax no longer applies, and they can be held accountable in the same way as an adult, subject to the jurisdiction of the Children’s Court.

There have been calls to raise the minimum age of criminal responsibility in Australia. Many argue that 10 years old is too young for a child to face the full force of the criminal law. The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child recommends that countries increase the minimum age to at least 14 years.

Some Australian states and territories have indicated they will move to raise the age. However, any change requires the agreement of all governments through the Council of Attorneys-General. For now, the principle of doli incapax remains an important protection for children who come into contact with the criminal justice system.

The Rationale Behind Doli Incapax

The doli incapax presumption exists in law for several important reasons that recognise the unique developmental stages and vulnerabilities of children.

Protecting Children’s Development

A key rationale behind the doli incapax presumption is the understanding that children mature and develop at varying rates, both intellectually and morally. The law acknowledges that children aged 10 to 14 are in the early stages of developing their capacity for reasoning, understanding consequences, and moral judgement.

Research shows that even children as old as 12 or 13 are still evolving their maturity and ability for abstract thinking. Their brains are not yet fully developed, particularly in areas related to impulse control, planning, and risk assessment. The presumption of doli incapax takes into account these individual differences in children’s development.

By presuming that children in this age group lack the capacity to be criminally responsible, the law avoids prematurely or unfairly imposing adult standards of understanding on children who may not have reached the necessary stage of moral development. It recognises that two children of the same age may have vastly different levels of understanding about right and wrong.

Balancing Justice and Child Welfare

Another important reason for the doli incapax presumption is the need to strike a careful balance between holding young offenders accountable and protecting the welfare of vulnerable children. The law aims to shield children from the full force of the criminal justice system when they may lack the maturity to fully understand the wrongfulness of their actions.

Exposing children to the trauma of arrest, police questioning, and criminal proceedings can have profound negative impacts on their wellbeing and future development. Even if a child is ultimately found doli incapax, significant harm may already have occurred through their contact with the criminal justice system.

The doli incapax presumption acts as a filter to ensure that only children who have clearly developed the capacity for criminal intent face the weight of full prosecution. For less mature children, it allows for alternative interventions focused on their welfare, rehabilitation and addressing the root causes of offending behaviour.

By diverting these children away from the criminal justice system, the presumption of doli incapax upholds the principle that the law should operate in the best interests of the child. It recognises that children have unique needs and vulnerabilities requiring a different approach than adults.

In summary, the rationale behind the doli incapax presumption is grounded in protecting children’s development and wellbeing while still allowing for accountability when their understanding of right and wrong is beyond doubt. It is a legal safeguard reflecting the complex realities of childhood maturity.

Get Immediate Legal Help Now.

Available 24/7

How is Doli Incapax Established?

The prosecution bears the onus of rebutting the presumption of doli incapax beyond reasonable doubt. This means they must prove the child knew their conduct was seriously wrong in a moral sense, not just naughty or mischievous.

The Prosecution’s Burden of Proof

To rebut the presumption of doli incapax, the prosecution must point to clear evidence from which an inference can be drawn that the child understood their actions to be seriously wrong. It is not enough to simply infer this from the commission of the act itself, no matter how obviously wrong it may seem to an adult.

The High Court in RP v The Queen emphasised that the presumption cannot be rebutted merely as an inference from the doing of the acts constituting the offence. The prosecution must adduce evidence that allows an inference to be drawn about the child’s development and their knowledge of the moral wrongness of their conduct.

Proving Knowledge of Moral Wrongness

Proving a child’s knowledge of moral wrongness requires more than showing they were aware the conduct was merely naughty or mischievous. The prosecution must demonstrate the child knew the conduct was “seriously wrong” or “gravely wrong”.

Relevant considerations include:

- The child’s intellectual and moral development

- The child’s education and the environment in which they have been raised

- Statements or admissions made by the child

- The child’s behaviour before and after the act

- The circumstances surrounding the offence

However, the High Court cautioned against making generalised assumptions about a child’s moral understanding based solely on their age or the type of act committed. The focus must be on the particular child’s actual knowledge that the conduct was seriously wrong, assessed in light of their unique attributes and circumstances.

How Can Doli Incapax be Rebutted?

To rebut the presumption of doli incapax, the prosecution must prove beyond reasonable doubt that the child knew their conduct was seriously wrong in a moral sense, not just naughty or mischievous. This requires evidence of the child’s development and understanding at the time of the alleged offence.

Types of Evidence Used

Various forms of evidence may be presented by the prosecution to try to rebut the presumption, including:

- Statements or admissions made by the child indicating their understanding of the moral wrongness of their actions

- The child’s behaviour before, during and after the alleged offence that suggests an awareness of guilt or wrongdoing

- The child’s prior criminal history, which may show past experience with the justice system and an understanding of right and wrong

- Evidence from parents, teachers or others regarding the child’s moral development, education and home environment

- Psychological or psychiatric reports assessing the child’s cognitive abilities and moral reasoning

The prosecution must show the child had actual knowledge of the serious wrongness of their conduct. It is not enough to argue a “normal” child of that age would have understood.

Challenges in Rebutting the Presumption

Prosecutors face significant hurdles in proving a child’s understanding of the moral wrongness of their actions:

- The child’s intellectual and moral development must be assessed as it was at the time of the alleged offence. Statements or evaluations made long after the incident may not accurately reflect their level of understanding when the conduct occurred.

- Even if a child admits wrongdoing after the fact, this may simply show they have since realised it was wrong, not that they understood at the time. Admissions must be carefully scrutinised for suggestibility or the impact of the arrest/court process.

- A child’s difficult upbringing, intellectual impairments or lack of moral education from parents can impact their ability to understand right from wrong. Background factors that diminish moral culpability must be considered.

- The mere fact a child tried to conceal their actions does not necessarily prove they understood the moral gravity, as opposed to just fearing punishment for misbehaviour. The circumstances as a whole must be examined.

Ultimately, rebutting doli incapax requires clear, convincing evidence directly establishing the individual child’s actual moral understanding at the time of the offence. Generalised inferences or assumptions about what a child “should have known” are not sufficient to displace this protective presumption.

The Leading Case: RP v The Queen

RP v The Queen is a landmark High Court case that clarified key principles regarding the doli incapax presumption. The case involved a boy who was accused of committing sexual offences against his younger brother when he was between 11 and 12 years old.

Key Findings of the Court

The High Court made several important rulings in RP v The Queen regarding the application of doli incapax:

- The prosecution bears the onus of rebutting the presumption of doli incapax beyond reasonable doubt. It cannot simply be inferred from the acts themselves, no matter how wrong they may seem.

- To rebut the presumption, the prosecution must show that the child knew the conduct was “seriously wrong” in a moral sense, not just “naughty or mischievous”.

- Evidence of the child’s education, background, and environment is relevant to determining whether they understood their actions to be morally wrong. Intellectual disability or exposure to inappropriate influences may impact moral understanding.

- The child’s age alone is not determinative. Children mature at different rates, so the capacity for moral reasoning must be assessed on a case-by-case basis.

Implications for Future Cases

The decision in RP v The Queen sets a high bar for prosecutors seeking to rebut the doli incapax presumption. It is not enough to simply prove that the child committed the acts or that the acts were obviously wrong by adult standards.

Instead, clear evidence must be presented that the individual child, taking into account their particular circumstances and level of development, understood the moral wrongness of their actions at the time. Generalised assumptions about what children of a certain age should know are not sufficient.

This means that in future cases, prosecutors will need to carefully consider what evidence can be brought to bear on the child’s moral capacities and understanding. Expert reports, school records, evidence from parents or teachers, and the specific circumstances of the offence may all be relevant.

At the same time, the case affirms the importance of the doli incapax presumption as a protection for children who may not yet have developed a mature understanding of right and wrong. It recognises that children can be vulnerable to external influences and may have reduced moral culpability even where they have committed acts that would be considered criminal in adults.

In summary, RP v The Queen provides important guidance for courts grappling with the complex question of when a child can be held criminally responsible. It emphasises the need for careful consideration of the individual child’s circumstances rather than reliance on preconceptions. The ruling will likely shape the handling of cases involving young defendants for years to come.

Speak to a Lawyer Today.

Available 24/7

Practical Considerations for Parents and Guardians

When a child under 14 is accused of a crime, parents and guardians face a challenging and stressful situation. Understanding the legal principles surrounding doli incapax is crucial for navigating the criminal justice system and protecting the child’s rights and well-being.

Seeking Legal Representation

One of the most important steps parents and guardians can take is to seek experienced legal representation for their child. A lawyer specialising in juvenile cases will have a deep understanding of the doli incapax presumption and how to effectively argue for its application. They can guide the family through the legal process, ensure the child’s rights are protected, and work to achieve the best possible outcome.

When choosing a lawyer, look for someone with a track record of successfully representing children in criminal cases. They should be able to clearly explain the legal concepts involved and develop a strong defence strategy tailored to the child’s specific circumstances.

Gathering Relevant Evidence

To support a doli incapax claim, parents and guardians can assist their legal team by gathering evidence that demonstrates the child’s level of maturity, understanding, and moral development at the time of the alleged offence. This may include:

- School records and teacher observations that provide insight into the child’s intellectual and social development

- Medical or psychological assessments that address the child’s cognitive abilities and emotional maturity

- Information about the child’s home life, upbringing, and any challenges or disadvantages they have faced

- Statements from family members, friends, or community members who can attest to the child’s character and level of understanding

It’s important to be proactive in collecting this information, as it can be critical in rebutting the prosecution’s attempts to prove the child understood the wrongfulness of their actions.

Parents and guardians should work closely with their legal team to identify the most relevant and persuasive evidence in their child’s case. By taking an active role in the defence process, families can increase the likelihood of a favourable outcome and ensure their child’s well-being remains a top priority throughout the legal proceedings.

The Debate Over Raising the Age of Criminal Responsibility of Children

In recent years, there has been growing discussion in Australia about increasing the minimum age of criminal responsibility. Currently, children as young as 10 can be arrested, charged, and imprisoned across the country. However, many argue that this age is too low and that children under 14 should be protected from the criminal justice system.

Arguments For and Against Change

Advocates for raising the age of criminal responsibility point to research showing that children’s brains are still developing, and they lack the maturity to fully understand the consequences of their actions. Exposing young children to the trauma of arrest and detention can have lifelong negative impacts. There are also concerns about the over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in the justice system.

On the other hand, some argue that there needs to be a way to hold children accountable for serious crimes and that raising the age will remove an important tool for addressing youth offending. There are also practical considerations around how to respond to children who exhibit very challenging behaviours if they cannot be charged with a criminal offence.

Potential Future Developments

Despite the ongoing debate, there is growing momentum for change. The ACT recently committed to raising the age of criminal responsibility to 14, and other states and territories are considering similar moves. At the national level, the Council of Attorneys-General has indicated support for developing a proposal to increase the minimum age, although consensus has not yet been reached on what the new age should be.

If the age of criminal responsibility is raised, it could have significant implications for how the legal system deals with children in conflict with the law. It may require an expansion of diversionary programs and therapeutic interventions to address the needs of these children without relying on criminal charges and detention. Raising the age may also interact with the presumption of doli incapax, as the age range to which the presumption applies could shift upwards.

Ultimately, any decision to raise the age of criminal responsibility will need to balance the rights and welfare of children with community safety considerations. It will require careful planning to ensure that adequate systems and supports are in place. However, many see reform in this area as an important step towards a more just and effective approach to youth justice in Australia.

Conclusion

Understanding the principle of doli incapax is crucial for parents and guardians navigating the criminal justice system with a child aged 10 to 14. This legal presumption recognises that children develop at different rates and may not fully comprehend the moral wrongness of their actions.

The High Court’s decision in RP v The Queen set a high bar for rebutting doli incapax. Prosecutors must provide clear evidence of the individual child’s moral understanding, not just assumptions based on age or the nature of the offence. As debates continue about raising the age of criminal responsibility, it’s vital for families to be aware of their rights and seek experienced legal representation if a child faces criminal charges.